Animals in the oeuvre of Mary Anne Barkhouse often appear as messengers, central figures cast in bronze, glass, or porcelain caught in tableaus reflecting on human interaction with the environment. Wildlife, in particular woodland creatures such as coyotes, beavers, rabbits and wolves, populate these narratives amid finely-made furniture referencing the early French and English colonial eras. Something is about to be stolen, broken, or bitten. Barkhouse’s work constantly places in opposition the natural world and that which would choose to dominate it. A Barkhouse mise-en-scène accentuates the latent violence and tension of the colonial encounter – the violent act has not yet occured. But the violence of colonization has happened, and is continuing to happen to Indigenous people, with the truth of the horrors of the ongoing colonial project in Canada being revealed to this very day.

Produced in 2008, Destrier was first exhibited at the Ottawa Art Gallery as part of a larger solo exhibition called Reins of Chaos. The exhibition comprised two installations, Destrier and The Four Horses of the Apocalypse and the Donkey of Eternal Salvation (2008). Each presented sculptures representative of the Four Horses of the Apocalypse from the New Testament’s Book of Revelations, heralding the Biblical idea of the end of the world. Symbolizing Conquest, War, Pestilence and Death, the Four Horses of the Apocalypse appear in two versions in the 2008 exhibition. On one hand they are coin-operated pop carousel horses evocative of a penny arcade, inviting visitors to ride them. On the other hand, with Destrier, they are subtle painted rocking horses in wood. These latter horses are the ones on view at Cassandra Cassandra.

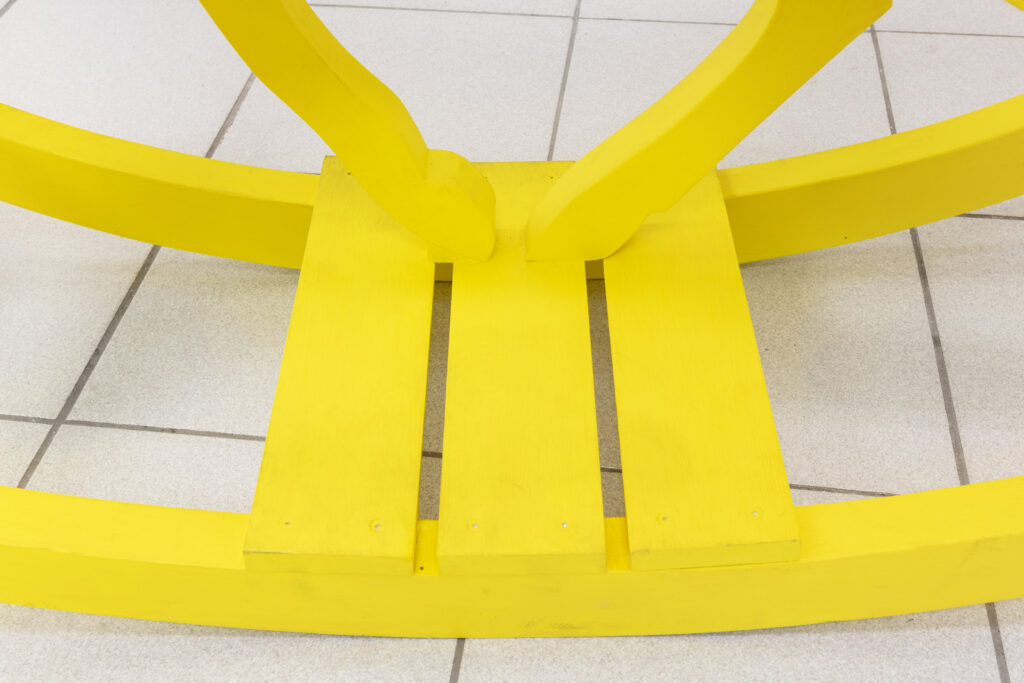

The title of the installation refers to the French word “destrier” which is the best-known war horse of the medieval era. They carried knights in battles, tournaments, and jousts. Interested in the different ways horses have been depicted throughout the last millennium, Barkhouse based the shape of the rocking horses upon images of warhorses sourced from works of art. The red one is taken from a manuscript produced by Beatus of Liebana, and illuminated by the Spanish monastery of Santo Domingo de Silos in the 12th century. The black one is based upon several images, such as historical paintings by Paul Kane. The yellow one was taken from a ledger drawing done by Assiniboine artist Hongeeyesa in 1885. Finally, the white one was saved by Barkhouse herself from the Minden Hills dump, restored and decorated with magnetic children’s numbers.

In the background, the wall is stenciled with a grid of military aircrafts and avian scavengers. The icons include the Nieuport 17, Spitfire, Lancaster, and CF-35 Joint Strike Fighter, as well as ravens and vultures. The combination of these stenciled icons demonstrates the extent to which military engineering mimics birds and thus the natural world. The military industrial complex camouflages itself in innocence.

Barkhouse has created an unsettling space reminiscent of a child’s bedroom with military wallpaper and apocalyptic toys. Emily Falvey notes that “In the context of Indigenous and European conflict, both bloody and ideological, Barkhouse’s use of primary colors, chalk-board paint, and learning toys like magnets cannot help but conjure the spectre of residential schools.” Destrier refers to early instances of war and violence among humans whose actions lead steadfastly to the dreaded end of the world.

As a member of the Nimpkish band, Barkhouse grew up with the creation story of the Kwakiutl First Nation. The story foregrounds the close link between human and animal life, and their mutual dependency on the natural resources of the earth. The Christian apocalypse narrative, to the contrary, nourishes an attitude seeking absolution and annihilation, eagerly awaiting the end of times. If the world we are living in is prophesied to be destroyed, what is the use of protecting it? In Barkhouse’s Kwakiutl tradition, there is no imminent end, and therefore no excuse for ecological and human neglect.

The figure of the horse illustrates perfectly the complex relationship between humans and animals and the evolution of human societies. The date of the horse’s domestication is still disputed, but is generally placed at around 5000 years ago somewhere in the eastern steppes of Eurasia. Even further back in history, horses were by far the most represented animals in palaeolithic cave art. The appropriation of this animal by humans revolutionized ancient societies, human mobility, and warfare.

The depiction of motion has been an undertaking of art since the beginning. In Gerald Vizenor’s essay “Native Cosmototemic Art” he writes about the animals painted on stone contours of cave walls, tying them to tricky narratives of resistance and survivance. He states that “The marvelous row of four horses in the Chauvet Cave scene anticipates the perspective and natural motion of many red, green and blue horses painted in the late nineteenth century by […] untutored native ledger artists”.

Barkhouse paid particular attention to the representation of movement to design the horses for Destrier. Referring to 19th century painting, she said: “I was looking at the way that horses were depicted at that time as running with all four feet spread out and off of the ground.” Horses have now become symbolic of the standard of excellence in illustrating an image of movement. Eadweard Muybridge, in 1878, photographed a horse in different stages of its gallop and “captured” its gait in a series of cabinet cards that, when viewed in quick succession, create the illusion of a horse in motion. This series is often cited as a precursor to contemporary motion pictures.

While balancing on a rocking horse, a child experiences a simulated horseback ride. Feigning actual travel, a rocking horse is pendulous and static. The object crystalizes the act of constraint. In Destrier, the rocking horses are riderless and all movement is impeded. Barkhouse winkingly twists the Four Horses of the Apocalypse to share her re-vision of history.

1 Hongeeyesa was an Assiniboine artist who lived in what is now southern Saskatchewan between 1860 and 1927.

2 Emily Falvey, Mary Anne Barkhouse: The Reins of Chaos, The Ottawa Art Gallery, 2008.

3 Gerald Vizenor. “Native Cosmototemic Art”, Sakahàn: International Indigenous Art. Greg A. Hill, Candice Hopkins, Christine Lalonde. Ottawa, ON: National Gallery of Canada, 2013, p. 43.

Mary Anne Barkhouse (b. 1961 in Vancouver, BC) has strong ties to both coasts as her mother is from the Nimpkish band, Kwakiutl First Nation of Alert Bay, BC and her father is of German and British descent from Nova Scotia. She is a descendant of a long line of internationally recognized Northwest Coast artists that includes Ellen Neel, Mungo Martin and Charlie James. She graduated with Honours from the Ontario College of Art in Toronto and has exhibited widely across Canada and the United States. She is well known for her public art installations that can be found in Toronto, Ottawa, Edmonton, Hamilton, London, Guelph, and Hull, among others.

As a result of personal and family experience with land and water stewardship, Barkhouse’s work examines ecological concerns and intersections of culture through the use of animal imagery. Inspired by issues surrounding empire and survival, Barkhouse creates installations that evoke consideration of the self as a response to history and environment.

A member of the Royal Canadian Academy of Arts, Barkhouse’s work can be found in numerous private and public collections.